Translation

Looking at difference between languages, anthropologists like Whorf missed the most important point: at a deep level, all human languages are similar to each other. Anything you can say in one human language can be translated into any

other human language (though not word for word).

The linguist Noam Chomsky said: a Martian scientist would view humans as speaking dialects of a single language.

Language isn't a clear window into thought even when no translation is involved.

so much depends upon

so much depends upon

a red wheel barrow

glazed with rain water

beside the white chickens.

- Wm Carlos Williams

Next: What is proper speech?

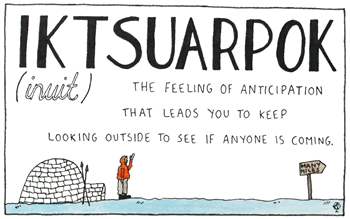

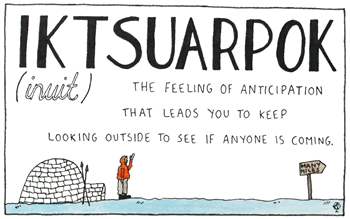

The point of the two illustrations: In the first, there is no English word that is equivalent to the Inuit word "iktsuarpok." But, this doesn't mean that therefore, we can never understand what people mean when they say that word. It just means that we need more words to translate a relatively simple idea. You probably don't know what the English word "persiflage" means either, but you can easily look it up. The second photo and poem illustrates a more difficult concept. It's the full text of the 1923 poem "The Red Wheelbarrow" by William Carlos Williams (1883-1963). This poem was widely acclaimed and endlessly reprinted. Generations of mid and late 20th century schoolkids (including me of course) learned it. You can hear Williams read it here. But, what does it mean? Can we truly know? Ideas about the translatability of language seem to presuppose that when people speak the same language they fully understand each other: that language is a true, accurate window into thought. But this simply isn't true. What did the poem mean to Wm Carlos Williams? What does it mean to you? Can I ever truly know the feelings and senses that the red wheelbarrow and white chickens evokes for another person? Our problem isn't that we can't fully understand what people say or write in another language. Our problem is that we can't fully understand what people say or write in our own language! This is not because we fail to use language correctly or lack understanding. It is a fundamental feature of language itself.

Consider the following famous passage from Through The Looking Glass.

...and that shows that there are three hundred and sixty-four days when you might get un-birthday presents—”

“Certainly,” said Alice.

“And only one for birthday presents, you know. There’s glory for you!”

“I don’t know what you mean by ‘glory,’” Alice said.

Humpty Dumpty smiled contemptuously. “Of course you don’t—till I tell you. I meant ‘there’s a nice knock-down argument for you!’”

“But ‘glory’ doesn’t mean ‘a nice knock-down argument,’” Alice objected.

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master—that’s all.”

Alice was too much puzzled to say anything, so after a minute Humpty Dumpty began again. “They’ve a temper, some of them—particularly verbs, they’re the proudest—adjectives you can do anything with, but not verbs—however, I can manage the whole lot of them! Impenetrability! That’s what I say!”

“Would you tell me, please,” said Alice “what that means?”

“Now you talk like a reasonable child,” said Humpty Dumpty, looking very much pleased. “I meant by ‘impenetrability’ that we’ve had enough of that subject, and it would be just as well if you’d mention what you mean to do next, as I suppose you don’t mean to stop here all the rest of your life.”

“That’s a great deal to make one word mean,” Alice said in a thoughtful tone.

“When I make a word do a lot of work like that,” said Humpty Dumpty, “I always pay it extra.”

“Oh!” said Alice. She was too much puzzled to make any other remark.

“Ah, you should see “em come round me of a Saturday night,” Humpty Dumpty went on, wagging his head gravely from side to side: “for to get their wages, you know.”

Humpty Dumpty goes on to attempt to explain the first stanza of "Jabberwocky." If you'd like to read his explanation you can find it here.

BUT, ultimately I've got to admit that the problem is more complex than these examples make it seem. A good really head-scratching case is language that describes senses. Ultimately, human beings are primarily visual animals. Estimates vary but conservatively about 30% of the human brain is vision related. At the same time, only a very small portion of the brain is used in smell and we only have about 1/3 the number of odorant receptors of a mouse. To some degree this is reflected in language. Many languages are substantially visual: that is there are many terms related to vision and people are able to describe what they see in detail without problem and with a high degree of agreement. This is much less true of the things that people smell. However, this is where it begins to get really interesting because, although human brains are all biologically the same, human languages are not. English has an extensive vocabulary describing color, but its vocabulary for smell, taste, and, touch is relatively impoverished. English speakers struggle to describe specific smells and almost always rely on metaphor (it smells like...). For example, here's how one English speaker described the smell of cinnamon in an experiment: “I don’t know how to say that, sweet, yeah; I have tasted that gum like Big Red or something tastes like, what do I want to say? I can’t get the word. Jesus it’s that gum smell like something like Big Red. Can I say that? Ok. Big Red. Big Red gum.” You can see that the person is struggling and the answer is idiosyncratic (Try it yourself. Describe the smell of gasoline without using the word "like."). Members of foraging cultures often have languages that are much better at describing smells and have many more words for them. The Jahai are foraging people who live around the border of Malaysia and Thailand and have an extensive vocabulary for smells. When they were asked to describe the smell of cinnamon, they responded with a single word and almost every Jahai asked the question used the same word. Now, on the one hand (a tactile metaphor), who cares? Obviously, both English speakers and Jahai can smell cinnamon and there is no reason to believe that the sensation of cinnamon is any different for Jahai speakers than for English speakers. On the other hand, would it be cognitively different to live in a world that had a dozen or so distinct names for scents? It's very, very hard to say. By the way, the Jahai word for the smell of gasoline is cŋɛs. Other things that smell cŋɛs include smoke, wild ginger root, and bat droppings. Again, on the one hand, these things most likely smell the same to all humans. On the other, cŋɛs is the same kind of word as "blue." That is, it's an abstract term describing a sensation. English speakers are very unlikely to smell gasoline, smoke, and bat droppings and automatically group them together in the same way they might instantly perceive a similarity between three blue objects.

so much depends upon

so much depends upon