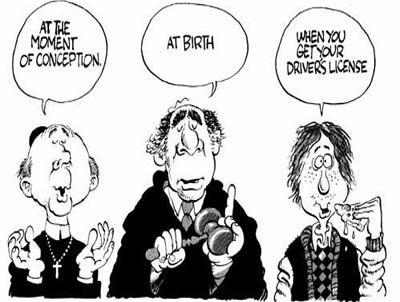

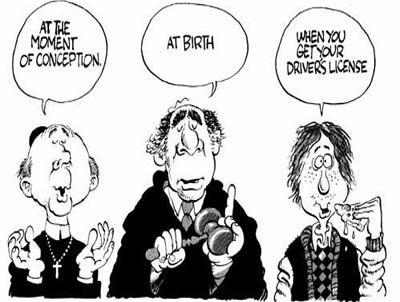

When does Human Life Begin?

An old joke says "when the kids go to college and the dog dies."

An old joke says "when the kids go to college and the dog dies."

Historically, most societies did not consider very young children to be fully human.

Their deaths were not mourned in the same way as deaths of older people and they were given little if any funerary treatment.

When human life begins is a social, not a biological fact.

Strangely (for us) in the history of humanity until recently, young people died more frequently than old people.

Next: On to swidden gardening

The idea that death is more associated with the young than with the old seems very odd to us, but it was a common fact until relatively recently. In most if not all societies before the last third of the 19th century, the mortality rate for people under 20 was between 40 and 50 percent. That is, between 40 and 50 percent of all children born alive would die before their 20th birthday. On the other hand, if you made it to your 30s, the odds that you would live to be 60 or 70 were reasonably good. The implication of this is that in these societies, the odds that a 50 year old would be alive in a year were much greater than the odds that a 10 year old would be.

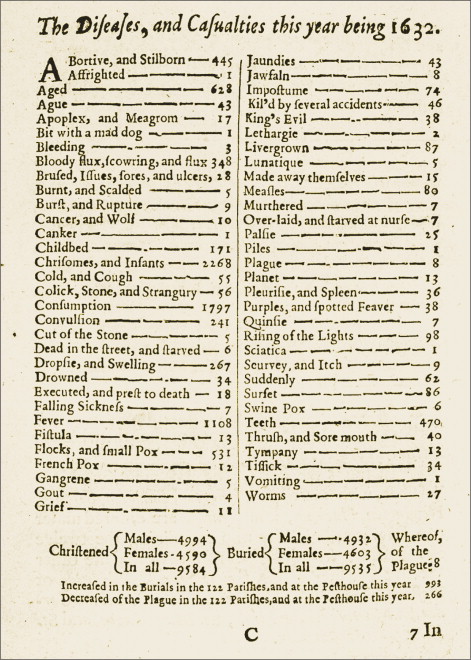

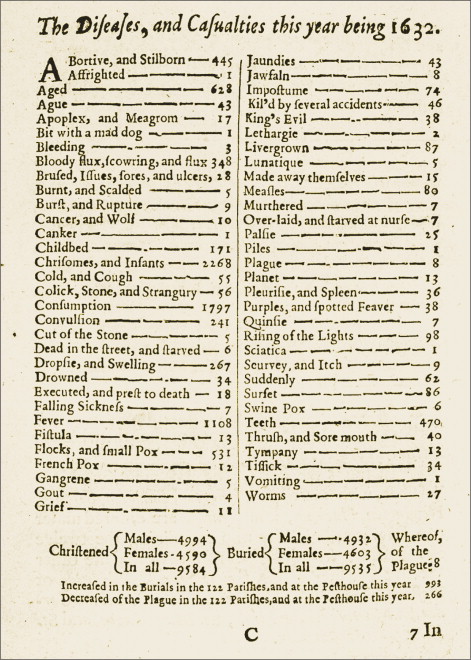

Consider this page from John Graunt's 1662 publication Natural and Political Observations made upon the Bills of Mortality.

It's kind of "fun" because it includes all sorts of sicknesses that we no longer recognize or at least no longer call by the same names. But, for our purposes look at the number of deaths of children and deaths related to childbirth: Abortive and Stillborn: 445, Childbed (women who died giving birth): 171, Chrisomes and Infants (a Chrisome was a child less than one month old): 2,268, Over-laid and starved: 7. So, in all, just shy of 3,000. Many of the categories not included in this total were probably under 20. For example, two of the highest categories are Bloody Flux (probably dysentery) and fever. Most of the victims of these were likely to have been young. Now compare to those judged to have died of old age, 628. And... this was before things started to get really bad. There were only about 250,000 people in London in the early 1600s. Things were going to get much worse as the city became more crowded. By 1800 the population had reached 1 million and the life expectancy at birth of the population was between 28 and 29! Life expectancy was higher outside of London where sanitary conditions were much better. There, life expectancy at birth was higher but still below 39. Across the UK, in 1800, about 1/3 of children died before reaching the age of five.

It's kind of "fun" because it includes all sorts of sicknesses that we no longer recognize or at least no longer call by the same names. But, for our purposes look at the number of deaths of children and deaths related to childbirth: Abortive and Stillborn: 445, Childbed (women who died giving birth): 171, Chrisomes and Infants (a Chrisome was a child less than one month old): 2,268, Over-laid and starved: 7. So, in all, just shy of 3,000. Many of the categories not included in this total were probably under 20. For example, two of the highest categories are Bloody Flux (probably dysentery) and fever. Most of the victims of these were likely to have been young. Now compare to those judged to have died of old age, 628. And... this was before things started to get really bad. There were only about 250,000 people in London in the early 1600s. Things were going to get much worse as the city became more crowded. By 1800 the population had reached 1 million and the life expectancy at birth of the population was between 28 and 29! Life expectancy was higher outside of London where sanitary conditions were much better. There, life expectancy at birth was higher but still below 39. Across the UK, in 1800, about 1/3 of children died before reaching the age of five.

The idea that the death of a child is an exception rather than a rule is only common anywhere in the world only since the last decade or so of the 19th century. One thing that separates us from our relatively recent fore bearers is that for just about all of us, the siblings and friends we had when we were in kindergarten were still around when we were in our 20s and 30s. Most families we know have not lost children.** This is a radical difference. For generations born before that (and many, many born though the first two thirds of the 20th century) loss of siblings and friends was the rule not the exception. It was a rare family that had not lost a child. A personal example: my great grandfather on my father's side was born in 1843. He lived in New York City. He had 9 children, but 4 of them died before the age of one. He was typical for his generation in this.

I don't think that people loved their children any less in societies where so many children died. We have lots of different sources of evidence that many parents experienced profound grief and depression. However, one critical difference is that this was a shared experience. Most people had experience of this sort of grief and people could come together in empathy and support one another. This is no longer true. Today, the loss of a child is often a not only an experience of grief but a profoundly isolating one as well.

One more comment on when life begins: Scientists don't really agree on exactly what life is let alone when it begins. We often (but not always) know when an individual organism is born or dies. But the quality " life" itself? That seems more like a continuous biochemical process that flows through the world.

Taking the question "When does Life Begin?" literally leads to a clear but challenging answer: Life begins more than 3.8 billion years ago. The "life" that is in you (and is in the tree outside your door, and is in your pets, and is in everything we think of as alive) has existed in an unbroken chain since that time. There has never been a point in the last 3.8 billion years when the life that is in you today was unambiguously not life. Consider egg and sperm for a second. Egg and sperm are, in and of themselves not an animal. They are not alive in the same way an animal is alive. However, they do clearly contain the quality of life, whatever that is. Consider a seed. A seed is obviously not a plant. However, it, somehow, contains the quality of life. A seed or egg and sperm are fundamentally different from things that are not alive, like a rock or a pencil. The quality of life in plants flows through the seed.* The quality of life in mammals flows through egg and sperm. To reiterate, the life of a human being (or any other living thing) has no "life begins." Life is always present, though we're not entirely clear on what it is. Thus far, although we've come tantalizingly close, we've never been able to create life from not-life.

The thing is, that in political and moral debates, people ask when life begins when they need to be asking when life is human. And, of course the problem is that the question "when does life begins" sounds (falsely) like it could has a scientific answer other than about 3.8 billion years ago. The question "when is life human" is clearly NOT a scientific question, but rather a moral and philosophical one. Different societies and different historical eras have given different answers to the question ranging from sperm and egg are morally human to (as the slide says) human life begins when the kids go to college and the dog dies. Maybe more troubling, different philosophical approaches to ethics give can give different answers as well. Broadly speaking there are three competing ethical schools: deontology (rule based ethics), consequentialism (ethics driven by the results of decisions, often linked to utilitarianism), and virtue ethics (what would the virtuous person do). Following these lines of thought people can come to diametrically opposed conclusions about when life is human and there is no (non political) was of deciding between them. So for example (and these are just examples... the same principles could be used to reach opposite conclusions) a deontologist might say there are absolute rules, dictated by my understanding of my religion, that say that human life begins at conception. A consequentialist might say, the goal of ethics is to increase human freedom and human happiness, women's control over reproduction clearly moves in this direction therefore it is best to understand human life as beginning at birth. A virtue ethicist might say the question of when human life begins must be weighed against the nature of that life and the circumstances of the sex act that led to it. There is no scientific way to decide among these three and in philosophy, people have quite literally been arguing about them for at least 2,500 years without decisive answer and will probably still be arguing 2,500 years from now.

If you would like to read a fascinating scientific treatment of the question, read Carl Zimmer's 2021 book Life's Edge: The Search for What It means to Be Alive.

*Of course, we are aware that plants and many (perhaps most) living creatures reproduce in non-sexual ways as well but for our argument here, we are focusing on sexual reproduction.

**There are exceptions. It may well be that the majority of families in certain areas of certain American cities, or certain areas in Appalachia and other regions have lost children to violence and drugs. Certainly in many places in the world, violence and brutality along with disease continue to make the death of children and young adults a common thing.

An old joke says "when the kids go to college and the dog dies."

An old joke says "when the kids go to college and the dog dies."

It's kind of "fun" because it includes all sorts of sicknesses that we no longer recognize or at least no longer call by the same names. But, for our purposes look at the number of deaths of children and deaths related to childbirth: Abortive and Stillborn: 445, Childbed (women who died giving birth): 171, Chrisomes and Infants (a Chrisome was a child less than one month old): 2,268, Over-laid and starved: 7. So, in all, just shy of 3,000. Many of the categories not included in this total were probably under 20. For example, two of the highest categories are Bloody Flux (probably dysentery) and fever. Most of the victims of these were likely to have been young. Now compare to those judged to have died of old age, 628. And... this was before things started to get really bad. There were only about 250,000 people in London in the early 1600s. Things were going to get much worse as the city became more crowded. By 1800 the population had reached 1 million and the life expectancy at birth of the population was between 28 and 29! Life expectancy was higher outside of London where sanitary conditions were much better. There, life expectancy at birth was higher but still below 39. Across the UK, in 1800, about 1/3 of children died before reaching the age of five.

It's kind of "fun" because it includes all sorts of sicknesses that we no longer recognize or at least no longer call by the same names. But, for our purposes look at the number of deaths of children and deaths related to childbirth: Abortive and Stillborn: 445, Childbed (women who died giving birth): 171, Chrisomes and Infants (a Chrisome was a child less than one month old): 2,268, Over-laid and starved: 7. So, in all, just shy of 3,000. Many of the categories not included in this total were probably under 20. For example, two of the highest categories are Bloody Flux (probably dysentery) and fever. Most of the victims of these were likely to have been young. Now compare to those judged to have died of old age, 628. And... this was before things started to get really bad. There were only about 250,000 people in London in the early 1600s. Things were going to get much worse as the city became more crowded. By 1800 the population had reached 1 million and the life expectancy at birth of the population was between 28 and 29! Life expectancy was higher outside of London where sanitary conditions were much better. There, life expectancy at birth was higher but still below 39. Across the UK, in 1800, about 1/3 of children died before reaching the age of five.