The Great Train Robbery v.

Voyage to the Moon

Today, they seem simple and unsophisticated but Both Voyage to the Moon (VTTM) and The Great Train Robbery (GTR) were important technical achievements in their era and both were revealing of the cultures that they came from and represented. We've been exposed to film and other media all of our lives so we have a unconscious understanding of how to tell a story with film, even if we've never really thought about it. People of the turn of the 20th century had no such experience. They really didn't know how to tell a story on film and they had no sense of what their audiences would or would not understand.

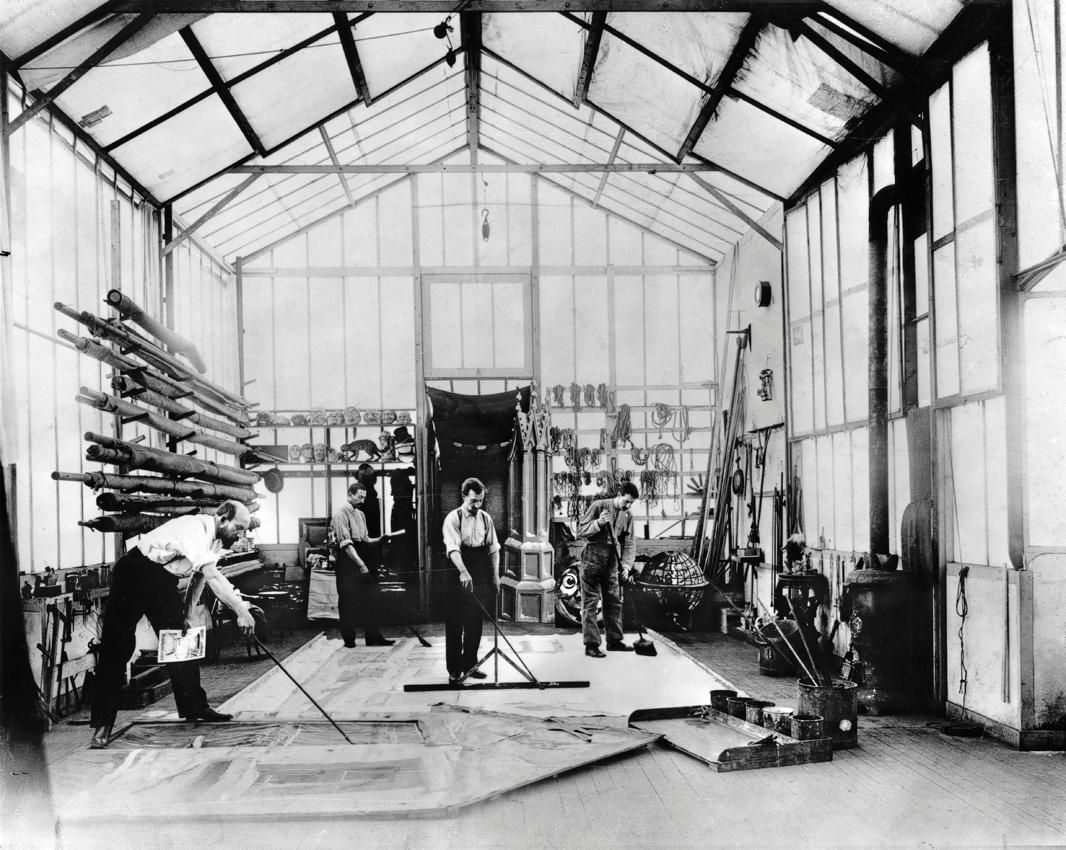

Melies VTTM is made a year before Porter and Edison's GTR. It showcases Melies' love of stage magic. It's full of neat special effects that look clunky to us but would have appeared magical to the audiences of 1903. The fundamental contribution VTTM makes is a demonstration that telling a story in film is something that happens in the editing room rather than in front of the camera. If you knew nothing about film, you'd probably think that the way you told a story on film was to just act out the story continuously while the camera runs. That's more or less what you see in the Edison film "Seminary Girls." However, there were two problems with this. First, the maximum amount of film that could be loaded in turn of the 20th century cameras was less than a minute. Second... well that's just not the way you do it. There are many other problems. What Melies did to create VTTM was to take a series of shots. All of his shots are quite simple in that they are taken with a camera in a fixed position pointing at either a stage or a set located in his studio (which was built to the same dimensions as his theater in Paris). Each of the shots was under a minute long. This process allowed him to set the stage and scenery however he wanted and film the shots in whatever sequence was most convenient. He then created the film by gluing the shots together in the correct order to tell the story. This enabled Melies to produce a film that ran about 13 minutes and told a complete story. This fundamental innovation, the idea that a movie is made up of shots and that a shot is the basic unit of storytelling has been a cornerstone of the movie industry ever since. Movies today are made up of thousands of shots taken at different locations and different times and assembled to tell a story. Really long shots, sometimes used to build tension, sometimes to show artistry, usually a little of both, are relatively rare and, when they work, celebrated. There are a few movies that are comprised of a single extremely long shot. The longest of these is Aleksandr Sokurov's 2002 film The Russian Ark which clocks in at 96 minutes.

Melies VTTM is made a year before Porter and Edison's GTR. It showcases Melies' love of stage magic. It's full of neat special effects that look clunky to us but would have appeared magical to the audiences of 1903. The fundamental contribution VTTM makes is a demonstration that telling a story in film is something that happens in the editing room rather than in front of the camera. If you knew nothing about film, you'd probably think that the way you told a story on film was to just act out the story continuously while the camera runs. That's more or less what you see in the Edison film "Seminary Girls." However, there were two problems with this. First, the maximum amount of film that could be loaded in turn of the 20th century cameras was less than a minute. Second... well that's just not the way you do it. There are many other problems. What Melies did to create VTTM was to take a series of shots. All of his shots are quite simple in that they are taken with a camera in a fixed position pointing at either a stage or a set located in his studio (which was built to the same dimensions as his theater in Paris). Each of the shots was under a minute long. This process allowed him to set the stage and scenery however he wanted and film the shots in whatever sequence was most convenient. He then created the film by gluing the shots together in the correct order to tell the story. This enabled Melies to produce a film that ran about 13 minutes and told a complete story. This fundamental innovation, the idea that a movie is made up of shots and that a shot is the basic unit of storytelling has been a cornerstone of the movie industry ever since. Movies today are made up of thousands of shots taken at different locations and different times and assembled to tell a story. Really long shots, sometimes used to build tension, sometimes to show artistry, usually a little of both, are relatively rare and, when they work, celebrated. There are a few movies that are comprised of a single extremely long shot. The longest of these is Aleksandr Sokurov's 2002 film The Russian Ark which clocks in at 96 minutes.

Edison and Porter's GTR relies on Melies use of shots as the basic devise of story telling but makes a series of innovations that represent major technical achievements. Some of these are combining on set and on location elements, innovative camera techniques like masking and double exposure, (famously) camera pan and tilt, and perhaps most importantly, parallel story plotting. While VTTM is essentially a filmed play, something that in principle you could see in a theater, GTR is fully "filmic." That is, it uses the special capacities of camera and film. While VTTM, particularly at the start, is a little confusing, GTR's story line requires no explanation. The use of parallel plot lines is probably the most important innovation. There are several different mini-stories happening simultaneously in GTR. 1) There's the story of the train robbery itself, 2) There's the story of the station-master and his daughter, 3) There's the story of the people at the dance, and finally 4) There's the story of vigilante justice at the end. The stories all overlap in time. The daughter discovers and revives her father while the train robbery is taking place. The dancers are dancing while the daughter is discovering her father and while the robbery is taking place. The pursuit by the vigilantes happens while the robbers are escaping. Piecing all of this film together correctly so that it could be easily understood by the audience was a major technical accomplishment.

Together, VTTM and GTR can be seen as proof of concept pieces. They showed how to tell a story in film and, perhaps more importantly, they showed that you could make money doing it. VTTM was a successful film and widely seen. GTR was a mega-hit of its era. First in the United States, and then abroad, it was seen repeatedly by a large percentage of the total population. It was shown at traveling shows and at state fairs. It was absolutely beloved by the masses. Neither Melies nor Porter followed them up with other similar films but many of their colleagues and competitors did. Very soon, the era of one-reeler films and nickleodeons took off.

VTTM and GTR were successful because they were well made, exciting to watch, and because people had never seen anything like them before. They had great novelty value. However, they were also successful because they tapped into cultural and national interests and they tapped into underlying cultural fears and dreams.

VTTM is a comic farce. You're not supposed to come away from it with deep thoughts about French culture and nationhood. As the saying goes, "you'll laugh, you'll cry, you'll kiss $10 (or in this case a few Francs) goodbye." However, it's the subtext that makes VTTM interesting as a cultural document. It appears in 1902, a high point of French colonialism, but also a point of self-examination and concern in French culture. Many in France felt that their culture was effete and decadent. They sometimes looked to the colonies for revitilization. For example a few years later, Charles Mangin, a colonial officer wrote a relatively famous book La Force Noire (1910) in which he argued for the use of troops drafted from France's African colonies to fight wars in Europe and elsewhere. His idea was that African strength would revitalize the French. This is an example of the ambivalence with which France viewed its colonies. On the one hand colonial populations were subjugated and the French felt superior to them. On the other hand they often believed that these colonized people were ultimately stronger, perhaps in the case of Mangin's African troops, more manly, than the French. A fantasy in which French astronauts both defeat moon people and run away from them seems to fit well with cultural themes.

GTR is a morality play. It's got live action excitement for its audience. But, it's ultimately the great-great-great-ancestor of tens if not hundreds of thousands of movies and TV shows that followed. A wrong is committed. The people who commit it are shown to be evil. In this case they attack the poor station-master, shoot the mail car attendant in cold blood, and shoot a passenger who tries to escape in the back. At least their motive is clear, they want money. The station-master, revived by his daughter, summons the townspeople who form a posse and head out after the robbers who are summarily killed. Justice is done. The bad guy robbers literally wear black hats and the good guy townspeople literally wear (mostly) white hats. The film fits in beautifully with the America of its era which was both highly moralistic and in which train robberies were in the news. The particular event often referred to as The Great Train Robbery was the 1866 robbery of an Ohio and Mississippi train in which the thieves stole about $7,000 cash (about 140k today) along with registered mail. However train robberies by The Wild Bunch (pictured left, which included Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid) were in the news in the late 1880s and 1890s. So, actually seeing a train robbery was thrilling to the audience.

There's another critical point about GTR. There's no question that audiences were supposed to and did cheer for the townspeople and boo the robbers. The robbers have no redeeming qualities. However, at a deeper level, this is a film about vigilante justice. There is no thought in the film that the robbers, whatever their crimes, might deserve due process of law. Instead, we're shown their murder by the townspeople and we're shown this as a good thing. There were numerous cases of vigilante murder in the US in the late 19th century including organized groups such as The Bald Knobbers who were responsible for many murders in the Ozarks in the decades following the Civil War. Extra-judicial killings, particularly of members of ethnic and racial minorities were relatively common at the turn of the 20th century, and violence, particularly against Black people peaked in the 1920s.

Now, Melies didn't intend VTTM to be a commentary on colonialism and Porter and Edison did not intend to make a statement about morality or about extra-judicial murder in GTR. I'm pretty sure that they never even thought about any of these things. They wanted to entertain people and to make money (not necessarily in that order). However, their films express the interests, attitudes, desires, and fears of their era. I don't know of any evidence that GTR increased vigilante justice in the US, but we can be pretty sure that it didn't decrease it either. It was the most popular film between its first showings in 1903 and 1912 and was seen by millions, probably by the majority of Americans alive in that era. The vast majority of them probably came away with the idea that justice was properly served.