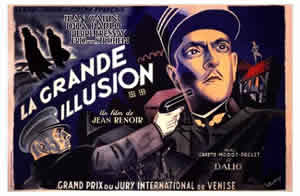

Grand Illusion (1937)

Grand Illusion, 1937, directed by Jean Renoir, written by Jean Renoir and Charles Spaak.

Grand Illusion, 1937, directed by Jean Renoir, written by Jean Renoir and Charles Spaak.

Grande Illusion is considered one of Renoir's greatest films. It was the first foreign language film nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture. It was banned by the fascists in Germany and Italy.

It is essentially a metaphor about the death of the old ruling class and social order.

A critical point: what exactly is the Grand Illusion of the title? No one in the film ever says anything like "and this is the Grand Illusion." BTW, this paradox repeats with The Rules of The Game (1939) in which no one ever directly mentions what the game is or the rules are. There are many possible non-exclusive answers to the questions within each film.

Grande Illusion is an anti-war film and an anti fascist film. It envisions the end of an older world order that, despite its attractions, was responsible for war and strife. It presents a Utopian dream of a world of the unification of opposites and the disappearance of both nations and war. However, Renoir is a realist. The optimism of the movie is a flickering candle, more likely to go out than to glow bright.

There are several key themes:

The aristocratic classes of Europe and their increasing irrelevance: De Boeldieu and von Rauffenstein represent the old aristocratic classes. They are both personally admirable characters. However, they are also part of the problem. Both are intelligent, to some degree empathetic, and absolutely honorable. However, despite their ability to think about their worlds, both are totally trapped by their roles. They fight as machines...they fight because they are programed by their societies to fight rather than because they have legitimate grievances. In fact, just the opposite is true: they are, or would be friends who understand each other and understand that they are one another's counterparts. In one of the movie's greatest scenes, von Rauffenstein clips the only flower in Wintersborn fortress. De Boeldieu is, of course, the flower. Von Rauffenstein and de Boeldieu also understand that their class is dying; that a new world will have no place for people like them. They fear becoming useless but note that they also accept this fatalistically. They don't believe they can change the course of history.

The rising social classes: Lieutenants Maréchal and Rosenthal represent the new rising classes of France. Maréchal is a worker, and engineer. Rosenthal is a wealthy entrepreneur but is Jewish. It is they who are ultimately the driving forces of the film. And, of course, it is they who are left at the end of the film. Their principal task is to overcome the differences between them. In a sense, they are the opposite of de Boeldieu and von Rauffenstein. They are to break with tradition and move toward a new and better society.

The illusory nature of seemingly obvious divisions: One of Renoir's key techniques is to show present thing that are, at least in theory, opposed to one another and then show that the similarities between them are far greater than the differences. This begins in the first scenes of the film. First we are shown French officers drinking and socializing at an officer's club. In the next scene we are shown German officers drinking and socializing at an officer's club. The similarity of the scenes is the point! Von Rauffenstein and de Boeldieu are opposites, yet the are far more similar to one another than either is to the men they command. Maréchal and Rosenthal are opposites: one working class and Christian, the other upper class and Jewish, but they too acknowledge solidarity with each other. Maréchal is a French soldier, Elsa is a German who has lost her family fighting the French but they become a couple. Even gender lines are blurred (remember, this is 1937). Maisonneuve, the French prisoner who dresses in women's clothing is far, far to realistic to the men who, though they know he is a man, are clearly attracted to him. And, of course, the de Boeldieu/von Rauffenstein bromance. Renoir's insistence on the illusory nature of division is key to the anti-authoritarianism of the film. One key aspect of authoritarian regimes, then as now, is an emphasis on divisions. Authoritarianism almost always requires and reinforces a us vs. them. Renoir insists that such divisions are illusory. The Nazis got this: they banned his films.

The irrelevance of national identity: Of course, one of the key points behind all of these others is Renoir's insistence that national identity, the thing he views as the main driving force of war, is an illusion. As we've seen repeatedly, relations between people united by social class or affection are more important than disjunctions that result from nationality. This is symbolized most perfectly at the end of the movie as the characters escape from Germany to Switzerland. Renoir has them crossing a field of snow with no physical barrier and no difference between one side and the other. He's suggesting that national barriers are products of the imagination. They have no physical reality other than that given to them by imagination.

BUT, these imaginary lines have devastating impacts on the fates of people. One of the most poignant aspects of the movie is that when all is said and done, Maréchal and Rosenthal are returning to France and they are knowingly returning to war. In doing so, Maréchal is potentially giving up he chance for love and for family as well. This is the bitter pill at the end of the movie. As I said at the start, Renoir is a Utopian but a depressive realist as well. Even though the characters have all realized the illusory nature of most divisions, especially nationalism, they still are trapped in a world where they will return to perhaps die for an illusion that their world, and perhaps ultimately they themselves, can't quite give up.

Of course the futility of war and the unreliability of reports about the war is a persistent theme through the movie. Perhaps the scene that best highlights this is von Rauffenstein describing his injuries. But, especially for audiences of the era of the film, many if not most of whom had experienced WWI, the early scenes in which Douaumont is first taken by the Germans and then retaken by the French had particular poignant The battles surrounding Douaumont were part of the Battle of Verdun (February to December 1916). Verdun was both extraordinarily bloody and extraordinarily futile. In all, there were more than 700,000 casualties including more than 300,000 dead. Douaumont was symbolic of its waste. It was easily captured by the Germans because the French hadn't thought much about it. It was undefended and no shots were fired. The French then spent 9 months and suffered hundreds of thousands of casualties winning it back. And in the end, it wasn't worth anything anyhow. Verdun changed nothing and the armies remained more or less in place.

Renoir uses Douaumont and some other clues to give us the time frame of the film. First we see the announcement that the Germans have captured Douaumont. That happened on Feb 25, 1916. A moment or two later in the film, we hear a false report that the French have retaken it, followed by a report that the Germans have retaken it. In reality, Douaumont wasn't recaptured by the French until October 24, 1916. Anyhow, that dates the capture of de Boeldieu and Maréchal and their experiences at the first camp to late 1915, and early 1916. When Maréchal and Rosenthal are about to escape, Maréchal tells de Boeldieu that they've been together 18 months. From other internal clues, we know that the last scene in the movie must occur in the spring of 1918. The war will go on until November 11th of that year. Renoir has thus left the ultimate fate and survival of Maréchal and Rosenthal ambiguous. I like to imagine that they took their time getting home...

Key Actors:

Erich von Stroheim (1885-1957) as Le captaine von Rauffenstein. Depending on the semester, von Stroheim may come up more than once in this class. Therefore, he's got his own page. Go to it by clicking here.

Jean Gabin (1904-1976) as le lieutenant Maréchal. Very well known French actor who had already appeared in 25 films by the time of Grande Illusion and would appear in another 70+ after. He became particularly well-known for playing Inspector Maigret (the hero of Georges Simenon's many novels) in the 1950s.

Pierre Fresnay (1897-1975) as le captaine de Boeldieu, another old hand who had been in movies since 1915, founded a theatre in Paris and stared in most of its plays.

Marcel Dalio (1899-1983) as le lieutenant Rosenthal. Dalio was born Israel Moshe Blauschild (His parents were Romanian Jewish immigrants to France). He also played in Renoir's Rules of the Game. (Robert de la Chesnaye, one of the key characters). He went on to become a very well known character actor (over 175 total film/TV acting credits both in US and France). When the Nazis invaded France, Dalio fled. Actually, his story has some overlap with the main story of Casablanca, a film in which both he and his wife appeared. In 1939, Dalio married the French actress Madeline Lebeau (1923-2016). When the Nazis invaded, the couple fled, by borrowed car and freight train to Lisbon, Portugal. There they were stuck waiting for... yup, letters of transit.* They eventually bribed an embassy official to provide the letters authorizing them to travel to Chile. They got as far as Mexico City when it was discovered the the letters were fake. Dalio and Lebeau quickly applied for asylum in numerous countries. It was Canada that eventually allowed them in. From there, through the efforts of American friends, he eventually came to Hollywood. Meanwhile, back in France, the Nazis used stills from Dalio's pictures to create a composite image of a "typical Jew" which they posted around Paris, instructing the citizens to alert the authorities should they see anyone who looked like that. Dalio's mother and his sisters were unable to escape and all were murdered in Auschwitz. Dalio and Lebeau both had long careers after they escaped the Nazis. As I mentioned, both appeared in Casablanca (Dalio as Emile the croupier, and Lebeau as Yvonne, Rick's mistress). Dalio also played across from Bogart in To Have and Have Not (1945). He appeared in many other films both in the United States and in France. Here he is in a famous scene in Catch-22 (1970):

Lebeau and Dalio didn't stay married long. They separated in 1942. Lebeau appeared in many films in the 1950s and 1960s. If you watched the Casablanca scene on the music page, you'll recognize Lebeau. Here's how she looks in that scene:

When Lebeau died in 2016 she was the last surviving credited cast member of Casablanca.

Film Reviews:

Roger Ebert review written in 1999 (required)

New Yorker review written in 2012 (required)

*The "yup" there assumes you've seen Casablanca IMHO still one of the greatest films of all time. If you haven't seen it, do so immediately, but here's the connection: Casablanca is really about the relationships between its main characters, Rick (Humphrey Bogart, Ilsa Lunc (Ingrid Bergman), Victor Laszlo (Paul Henreid) and Louis Renault (Claude Rains). However the plot concerns two letters of transit that will allow the people holding them to leave Casablanca and fly to Portugal, escaping Nazi control. The letters have been stolen from a German courier by Ugarte (Peter Lorre) and given to Rick for safe keeping. Ugarte is murdered by the Nazis, leaving Rick in possession of the papers of transit. The key issue for the rest of the movie is who will use them: Rick and Ilsa or Victor Laszlo and Ilsa.

Next: Italian Neo-realism