Cinematography Terms

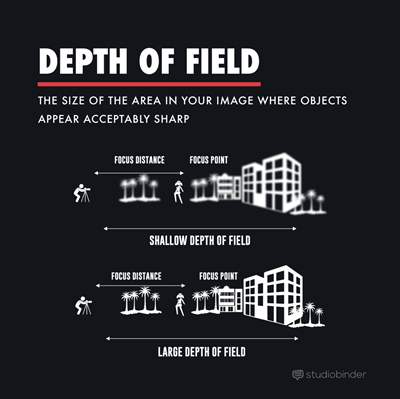

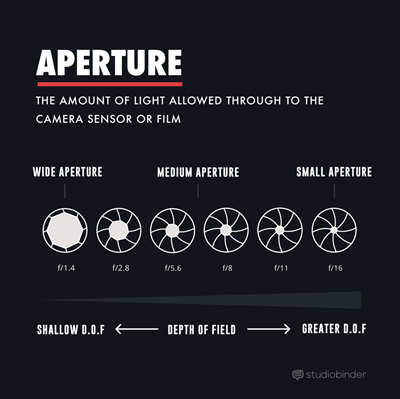

DEPTH OF FIELD

The zone of acceptable sharpness within a frame that will appear in in focus. Every picture has a zone in front of and behind the subject that will appear in focus. Bright light and a narrow lens aperture tend to produce a larger depth of field (meaning a greater area in which things are in focus), as does using a wide-angle lens. Conversely, a wide lens aperture or a telephoto lens tend to produce a smaller depth of field. Depth of field is directly connected to, but should not be confused with, focus. Focus is the quality of an image (the “sharpness” of an object as it is registered in the image) and depth of field refers to the extent to which the space represented is in focus.

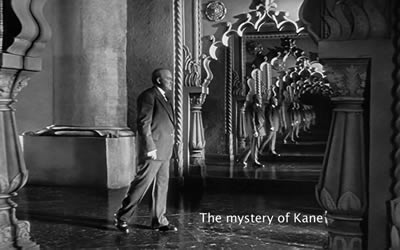

DEEP FOCUS

Deep focus is a style or technique of cinematography and staging that uses relatively wide angle lenses and small lens apertures to render in sharp focus near and distant planes simultaneously. A deep-focus shot includes foreground, middle-ground, and extreme-background objects, all in focus. Deep focus gives a sense of depth. Citizen Kane (1941) is famous for its deep focus shots. Here's one that suggests Kane's self absorbtion:

Here's a modern example from Wonder Woman (2017)

SHALLOW FOCUS

Shallow focus is a photographic and cinematographic technique that keeps one plane of an image in focus while the rest is out of focus. It uses large lens apertures which keep only one plane in sharp focus. It's the opposite of deep focus. It is used to direct the viewer’s attention to one element of a scene. Shallow focus is very common in close-up, as in these two shots from Central Station (Central do Brasil, Walter Selles, Brazil, 1998).

PAN

A camera movement with the camera body turning to the right or left on a stationary support. On the screen it produces a mobile framing which scans the space horizontally. A pan connects two places or characters making us aware of their proximity and relationship. Here's an example of a fast pan from Traffic (2000):

TILT

A camera movement with the camera body moving upward or downward on a stationary support. On the screen it produces a mobile framing which scans the space vertically. Like a pan, a tilt can connect two characters. In this tilt from Besieged (1998) it connects a maid and her employer.

TRACKING SHOT

A moble framing that travels through space forward, backward, or laterally. This is a basic element of cinematography in most movies and there are lots of ways to accomplish it. In fact, many of the remaining terms (like Following Shot) use one or another tracking techniques. In early movies, creating a tracking shot often literally involved setting up a track and having the camera, mounted on a dolly, move along the track parallel to the action. This technique is still often used.

![]()

Here's a nice example of a tracking shot (I'm not sure where this is taken from). First, the camera, on a dolly and track, follows the movement of the little girl. Then, the camera, using the train itself, tracks the girl.

FOLLOWING SHOT

A shot with framing that shifts to keep a moving figure onscreen. A following shot uses movement to direct our attention to a character or object as he/she/it moves inside the frame. Here's a great example from Alfred Hitchcock's North by Northwest (1959):

POINT-OF-VIEW SHOT/EDITING

A shot taken with the camera placed approximately where the character’s eyes would be, showing what the character would see; usually cut in before or after a shot of the character looking. Horror films and thrillers often use POV shots to suggest a menacing and unseen presence in the scene. Films that use many point-of-view shots tend toward dynamic and non-naturalistic style. POV is one of the means by which audiences are encouraged to identify with characters. You can think of POV as being both a type of shot and a type of editing technique. Here's an example from Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo (1958). You'll see that it's the editing that really makes it work.

CRANE SHOT

A shot with a change in framing rendered by having the camera above the ground and moving through the air in any direction. It is accomplished by placing the camera on a crane (basically, a large cantilevered arm) or similar device. Crane shots are often extreme long shots: they lend the camera a sense of mobility and often give the viewer a feeling of omniscience over the characters. Here's a shot from Robert Altman's The Player (1992).

STEADICAM

Steadicams are cameras mounted on complex stabilizing harnesses that allow the operator to walk while producing smooth camera movement. Steadicams offer an inexpensive way to simulate traditional dolly based tracking (and are capable of many shots that tracking can't capture).

Maybe the single most famous example of a steadicam shot is this unusually long tracking shot from Goodfellas (1990). Take a moment (or the three that it takes to watch this shot) and consider just how difficult this is to do. Consider the number of people who must perform their actions flawlessly, the amount of floor space that must be lit, the amount of tech that is involved to get everything just right. It's not surprising that oners like this are highly prized by Hollywood insiders and critics. If you'd like to see a great comic take on oners, watch Season 1, Episode 2 of The Studio (2025).

HAND HELD CAMERA

Handheld camera shots are pretty much just what they sound like: the camera is simply held by the operator without the use of a tripod or other base. Handheld shots produce jerky motion that emphasizes the immediacy of a scene. Here's a hand held shot from Blair Witch Project (1999).

Next: Editing Terms