Black Film making in the US

Almost from the beginning of the film industry, African Americans attempted to make films that were written by Black authors, had Black stars and were aimed primarily at Black audiences. These are sometimes called "race films." More than 500 were made but very few survive. Like the rest of the early film industry, the early Black film industry relied heavily on vaudeville and the circuits of theaters established by T.O.B.A.

Until at least the last third of the 20th century, making films for African-American audiences was generally a bad economic proposition. Distribution opportunities were very limited and audiences had little money. Movie theaters were strictly segregated. In the South, segregation was legally enforced. Black audience members often had their own entrance and were confined to the balcony or the back of the theater. In the North, segregation was a matter of custom rather than law but Black audience members were almost as restricted as they were in the South. Theaters that had primarily white audiences rarely showed race films (though sometimes, if they were located in places where there were large Black populations, they had special matinees or midnight showings). A "Blacks only" film circuit also developed: a series of small theaters that catered exclusively to Black people (The Gem, photo left, was in Waco). In addition, movies made for Black audiences were often shown at African American churches.

Until at least the last third of the 20th century, making films for African-American audiences was generally a bad economic proposition. Distribution opportunities were very limited and audiences had little money. Movie theaters were strictly segregated. In the South, segregation was legally enforced. Black audience members often had their own entrance and were confined to the balcony or the back of the theater. In the North, segregation was a matter of custom rather than law but Black audience members were almost as restricted as they were in the South. Theaters that had primarily white audiences rarely showed race films (though sometimes, if they were located in places where there were large Black populations, they had special matinees or midnight showings). A "Blacks only" film circuit also developed: a series of small theaters that catered exclusively to Black people (The Gem, photo left, was in Waco). In addition, movies made for Black audiences were often shown at African American churches.

Between 1910 and 1918, there were 13 Black film companies. However, most of these made only one film each. William Foster (pictured left) is generally considered the first Black director. He established Foster Photoplay in Chicago in 1910. His best known film is probably The Railroad Porter (1912). However, he made several others. All of Foster's films have been lost (though some footage was discovered in 2014). Foster had a strong ideological vision. He believed both that Black people needed to represent themselves on film and that they could improve their social and economic position by doing so.

Between 1910 and 1918, there were 13 Black film companies. However, most of these made only one film each. William Foster (pictured left) is generally considered the first Black director. He established Foster Photoplay in Chicago in 1910. His best known film is probably The Railroad Porter (1912). However, he made several others. All of Foster's films have been lost (though some footage was discovered in 2014). Foster had a strong ideological vision. He believed both that Black people needed to represent themselves on film and that they could improve their social and economic position by doing so.

Noble Johnson (1881-1978) was another important early African American film maker. Johnson, with his brother George, was the founder of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company. Lincoln was founded in Nebraska but moved to LA. Johnson starred in most of its early films. Lincoln made and distributed at least five films including two full length features. Almost all of Lincoln's production has been lost, including its first film The Realization of a Negro's Ambition (1916). About four minutes of the hour long By Right of Birth (1921) exists today. Like Foster, Johnson believed in the power of film to improve the image and position of African Americans. However, Johnson unsuccessfully searched for wide distribution for its films. They were shown only in Black churches and "Colored Only" movie theaters. Like Foster Photoplay, Lincoln was not financially successful. Johnson himself moved from Lincoln to Universal. He went on to play in many films from the 20s through the 40s. Johnson sometimes played African-American parts but just as often was cast as Native American, Latino, or Arab.

Noble Johnson (1881-1978) was another important early African American film maker. Johnson, with his brother George, was the founder of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company. Lincoln was founded in Nebraska but moved to LA. Johnson starred in most of its early films. Lincoln made and distributed at least five films including two full length features. Almost all of Lincoln's production has been lost, including its first film The Realization of a Negro's Ambition (1916). About four minutes of the hour long By Right of Birth (1921) exists today. Like Foster, Johnson believed in the power of film to improve the image and position of African Americans. However, Johnson unsuccessfully searched for wide distribution for its films. They were shown only in Black churches and "Colored Only" movie theaters. Like Foster Photoplay, Lincoln was not financially successful. Johnson himself moved from Lincoln to Universal. He went on to play in many films from the 20s through the 40s. Johnson sometimes played African-American parts but just as often was cast as Native American, Latino, or Arab.

Oscar D. Micheaux (1884-1951) was almost certainly the most successful producer of films by and about Black people in the first half of the 20th century. Sometimes referred to as the Czar of Black Hollywood, Micheaux was an entrepreneur at an early age. He was variously a shoeshine boy, a Pullman porter, a South Dakota homesteader, a novelist, a book publisher, a door-to-door salesman of his own books, and finally the owner of the Micheaux Film and Book Company. The film company began when the Johnson brothers tried to buy the rights to Micheaux's 1917 novel The Homesteader. Micheaux did not approve of the way they wanted to make the film so he organized his own company to make it. The Homesteader, based on Micheaux's experiences, appeared in 1919 (and is a lost film). For his second film, Micheaux made Within Our Gates(1920), a direct response to Birth of a Nation. Micheaux's scripts were not particularly well crafted and the production values of his films were low. But, they were very popular with Black audiences. He went on to make 44 films, both writing and directing most of them. He made films of all types, musicals, romances, comedies, and gangster films. Micheaux's films often tackled hard issues: white racism, economic and social injustice, and violence against African-Americans. However, Micheaux also always cast lighter skinned people as heroes and heroines and darker skinned people as heavies and villains. Numerous Micheaux films survive including Within Our Gates (1932), God's Step Children (1938) and Lying Lips (1939). You can see Within Our Gates and Lying Lips by clicking on the links.

Oscar D. Micheaux (1884-1951) was almost certainly the most successful producer of films by and about Black people in the first half of the 20th century. Sometimes referred to as the Czar of Black Hollywood, Micheaux was an entrepreneur at an early age. He was variously a shoeshine boy, a Pullman porter, a South Dakota homesteader, a novelist, a book publisher, a door-to-door salesman of his own books, and finally the owner of the Micheaux Film and Book Company. The film company began when the Johnson brothers tried to buy the rights to Micheaux's 1917 novel The Homesteader. Micheaux did not approve of the way they wanted to make the film so he organized his own company to make it. The Homesteader, based on Micheaux's experiences, appeared in 1919 (and is a lost film). For his second film, Micheaux made Within Our Gates(1920), a direct response to Birth of a Nation. Micheaux's scripts were not particularly well crafted and the production values of his films were low. But, they were very popular with Black audiences. He went on to make 44 films, both writing and directing most of them. He made films of all types, musicals, romances, comedies, and gangster films. Micheaux's films often tackled hard issues: white racism, economic and social injustice, and violence against African-Americans. However, Micheaux also always cast lighter skinned people as heroes and heroines and darker skinned people as heavies and villains. Numerous Micheaux films survive including Within Our Gates (1932), God's Step Children (1938) and Lying Lips (1939). You can see Within Our Gates and Lying Lips by clicking on the links.

Not all producers of race films were Black. For example the Colored Players Film Corporation was founded by David Starkman (1885-1947), who was white and who owned "colored only" theaters in Philadelphia. CPFC made four feature films, two of which have been lost. After releasing films in 1926, Starkman joined forces with Dudley Sherman, the Black vaudevillian and circuit owner. Together they made The Scar of Shame (1927), the studio's most successful film. It dealt with class differences within the Black community. CPFC films had relatively high production values. They dealt with real issues, showed Black people as heroes and heroines, and were very well received in Black communities. However they did not take on white racism or critical racial issues such as violence against Black people.

Not all producers of race films were Black. For example the Colored Players Film Corporation was founded by David Starkman (1885-1947), who was white and who owned "colored only" theaters in Philadelphia. CPFC made four feature films, two of which have been lost. After releasing films in 1926, Starkman joined forces with Dudley Sherman, the Black vaudevillian and circuit owner. Together they made The Scar of Shame (1927), the studio's most successful film. It dealt with class differences within the Black community. CPFC films had relatively high production values. They dealt with real issues, showed Black people as heroes and heroines, and were very well received in Black communities. However they did not take on white racism or critical racial issues such as violence against Black people.

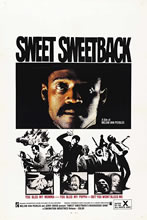

As legal segregation disappeared in the United States, so did the race films. On the one hand, the end of legal segregation was unquestionably something to be celebrated. On the other, the end of race films also meant the decline of Black filmmakers, of films with predominantly or entirely Black casts, and of films seriously addressing issues of race. These later did not completely disappear. In the 50's and 60's there were Imitation of Life (1959), A Raisin in the Sun (1961), To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), and In the Heat of the Night (1967). The good news: all these were serious, major films seen by millions. The bad: none were produced or directed by Black people and only Raisin in the Sun had a predominantly Black cast. The next major film with a Black director and predominantly Black cast was Melvin Van Peebles (1932-2021)1 Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song (1971). Van Peebles had made several films before his but this was the first he controlled. He funded it with his own money and a loan from Bill Cosby. It opened at only two theaters but went on eventually to gross over $15 million. It was the beginning of the Blaxploitation films of the 1970s.

As legal segregation disappeared in the United States, so did the race films. On the one hand, the end of legal segregation was unquestionably something to be celebrated. On the other, the end of race films also meant the decline of Black filmmakers, of films with predominantly or entirely Black casts, and of films seriously addressing issues of race. These later did not completely disappear. In the 50's and 60's there were Imitation of Life (1959), A Raisin in the Sun (1961), To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), and In the Heat of the Night (1967). The good news: all these were serious, major films seen by millions. The bad: none were produced or directed by Black people and only Raisin in the Sun had a predominantly Black cast. The next major film with a Black director and predominantly Black cast was Melvin Van Peebles (1932-2021)1 Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song (1971). Van Peebles had made several films before his but this was the first he controlled. He funded it with his own money and a loan from Bill Cosby. It opened at only two theaters but went on eventually to gross over $15 million. It was the beginning of the Blaxploitation films of the 1970s.