Beauty Knows No Pain (1971)

Beauty Knows No Pain is a 1971 film by Elliott Erwitt (1928-2023). Erwitt was one of the best known photographers of the post-war 20th century and worked well into the 21st. He was primarily a still photographer but he made several movies as well. You can see a collection of some of Erwitt’s most famous photos HERE. Erwitt particularly loved photographing dogs and published several books of pictures of them. As you watch Beauty Knows No Pain, keep one of the best known things Erwitt said in mind: “I’ve found [photography] has little to do with the things you see and everything to do with the way you see them.”

Erwitt’s vision was always humane and often really funny and ironic. This is evident in Beauty Knows No Pain. Throughout the film, it is clear that Erwitt is amused by the Rangerettes. He films them and edits them in ways that emphasize the humor, oddness, and sometimes the silliness of what they are doing. But you can see that he is also somehow impressed by them. It’s a film that makes you think about drill teams such as the Rangerettes and especially about Gussie Nell Davis (GND), their leader. But it doesn’t say anything hateful or nasty.Throughout the film, Erwitt lets Gussie Nell, and the girls speak for themselves. There is no narration or titles. It’s all “in their own words.” The humor and the commentary come entirely from the choices that Erwitt makes, the elements that he shows, and the way he shoots and combines them. Remember when you watch this and any film that cameras are incapable of showing the truth. It never shows the things you see, always the way you see them.

Remember that Beauty Knows No Pain is not an account of the days that Erwitt spent with the Rangerettes in 1970. It’s a 20-minute film, edited out of the hours of film that he shot during those days. And those hours captured only a small portion of what went on during that time. So, like any film, Beauty Knows No Pain is entirely constructed.

Let’s look at a half dozen scenes and consider how they are put together and the choices that Erwitt makes.

The opening sequence. It’s early morning, not long after sunrise. The girls march onto the field. The music is “Battle Hymn of the Republic” played horribly (presumably it’s slowed down to get the timing that GND needs for the routine, but no one tells us that. It’s just horrible-sounding music). Erwitt uses camera angles from hip level to low shots. The low shots make the girls loom on the screen and Erwitt focuses on girls who have large rollers in their hair. On the one hand, it shows their dedication. They’re out on the field in states of semi-dress that they would not usually appear in in public. On the other, it looks silly. The opening is an odd combination of seriousness and silliness and that will continue through the movie. Erwitt continues by cutting to a closeup of GND dramatically describing the origins of the Rangerettes. Her account is amusing, and this is heightened by her appearance, particularly the rhinestone pointed glasses she wears.

The opening sequence. It’s early morning, not long after sunrise. The girls march onto the field. The music is “Battle Hymn of the Republic” played horribly (presumably it’s slowed down to get the timing that GND needs for the routine, but no one tells us that. It’s just horrible-sounding music). Erwitt uses camera angles from hip level to low shots. The low shots make the girls loom on the screen and Erwitt focuses on girls who have large rollers in their hair. On the one hand, it shows their dedication. They’re out on the field in states of semi-dress that they would not usually appear in in public. On the other, it looks silly. The opening is an odd combination of seriousness and silliness and that will continue through the movie. Erwitt continues by cutting to a closeup of GND dramatically describing the origins of the Rangerettes. Her account is amusing, and this is heightened by her appearance, particularly the rhinestone pointed glasses she wears.

-

GND berates the girls. In this scene, GND shows the girls the ways they look on a television monitor. She’s almost screaming at the girls but this is countered by the way she looks wearing broadly striped pants (admittedly more fashionable 50 years ago than now but Erwitt is still going for the visual effect of her with on foot on the stage and the other on the chair). This is heightened still further by the absurdity of what she’s saying: “We’re going to say one TWO and we’re going to say one two if we’ve got to stay here until midnight to do it.”

GND berates the girls. In this scene, GND shows the girls the ways they look on a television monitor. She’s almost screaming at the girls but this is countered by the way she looks wearing broadly striped pants (admittedly more fashionable 50 years ago than now but Erwitt is still going for the visual effect of her with on foot on the stage and the other on the chair). This is heightened still further by the absurdity of what she’s saying: “We’re going to say one TWO and we’re going to say one two if we’ve got to stay here until midnight to do it.”

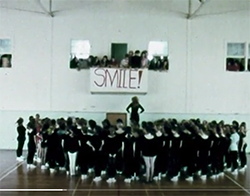

This is followed by what I think is the funniest and most provoking scene in the film. GND appears on a balcony above a sign that says “Smile” and she shouts “Discipline, discipline yourselves, Discipline.” I wish I could take credit for the phrase, but years ago, a student in this class called GND a “smile Nazi” and that’s exactly right. In this scene, she appears as the Italian Fascist leader Mussolini, who repeatedly gave speeches from his balcony. Hitler too was fond of balconies. I think Erwitt is probably falling out of his chair laughing at this point.

This is followed by what I think is the funniest and most provoking scene in the film. GND appears on a balcony above a sign that says “Smile” and she shouts “Discipline, discipline yourselves, Discipline.” I wish I could take credit for the phrase, but years ago, a student in this class called GND a “smile Nazi” and that’s exactly right. In this scene, she appears as the Italian Fascist leader Mussolini, who repeatedly gave speeches from his balcony. Hitler too was fond of balconies. I think Erwitt is probably falling out of his chair laughing at this point.

-

The Beauty Knows No Pain Smile. GND narrates about how important smiles are and how much fun the girls have as the camera holds a closeup of one Rangerette smiling for almost 45 seconds. The audience sees that this is clearly not fun, it’s desperately difficult. This leads to what is probably GND’s finest moment in the film. She appears in front of the girls, almost pleading “say I’m beautiful, come on say it. With your face, with your body, say I’m beautiful.” On the one hand GND’s values are shallow and demeaning. Later she talks about how a Rangerette will always get any job she applies for because employers know that she will always look good. But, in the moment she tells the girls to say they’re beautiful the audience sees that she really cares deeply about these women and is talking about self-confidence in a way that is almost modern.

The Beauty Knows No Pain Smile. GND narrates about how important smiles are and how much fun the girls have as the camera holds a closeup of one Rangerette smiling for almost 45 seconds. The audience sees that this is clearly not fun, it’s desperately difficult. This leads to what is probably GND’s finest moment in the film. She appears in front of the girls, almost pleading “say I’m beautiful, come on say it. With your face, with your body, say I’m beautiful.” On the one hand GND’s values are shallow and demeaning. Later she talks about how a Rangerette will always get any job she applies for because employers know that she will always look good. But, in the moment she tells the girls to say they’re beautiful the audience sees that she really cares deeply about these women and is talking about self-confidence in a way that is almost modern.

-

North Dakota: There is only one extended interview of a Rangerette shown in the film. An unnamed girl who we’ll call North Dakota (ND) gets quite a bit of time. Remember, we do not know how many interviews Erwitt filmed. We only know he chose this one to present. It’s an interesting choice. First, there is the visual aspect. ND looks like a Heidi doll. This is a film that shows only white people, but this girl is whiter than white. Second, she seems extremely provincial and naïve, and maybe not too bright. Third, she whines a little but is entirely conformist. She essentially says, yes, I didn't like being hazed and tortured as a freshman but now I'm all for it. This gives us a specific perspective on the kinds of people who join the Rangerettes. But remember that we really know nothing of either ND or the other girls. For all we know they went on to become doctors, lawyers, entrepreneurs, and artists.

North Dakota: There is only one extended interview of a Rangerette shown in the film. An unnamed girl who we’ll call North Dakota (ND) gets quite a bit of time. Remember, we do not know how many interviews Erwitt filmed. We only know he chose this one to present. It’s an interesting choice. First, there is the visual aspect. ND looks like a Heidi doll. This is a film that shows only white people, but this girl is whiter than white. Second, she seems extremely provincial and naïve, and maybe not too bright. Third, she whines a little but is entirely conformist. She essentially says, yes, I didn't like being hazed and tortured as a freshman but now I'm all for it. This gives us a specific perspective on the kinds of people who join the Rangerettes. But remember that we really know nothing of either ND or the other girls. For all we know they went on to become doctors, lawyers, entrepreneurs, and artists. -

The Vote: Toward the end of the film, we see the girls voting on who will be asked to join the team. Most people see this as a scene demonstrating the conformity that the Rangerettes demand. The girls have clearly mastered GND’s vocabulary and the girl who is running the vote clearly dominates the conversation. The other girls fall in line in support of her. The votes are taken by show of hands and that provides additional pressure to conform. If you vote in opposition to the leader, you must do so publicly. However, it is also interesting that the Rangerettes, at least in that year, seemed to be self-governing with, perhaps, the members rather than GND determining who was asked to join (though, again, we don’t know this. It’s likely that the members submitted their choices to GND who then decided if there were people she wanted to add or strike).

The Vote: Toward the end of the film, we see the girls voting on who will be asked to join the team. Most people see this as a scene demonstrating the conformity that the Rangerettes demand. The girls have clearly mastered GND’s vocabulary and the girl who is running the vote clearly dominates the conversation. The other girls fall in line in support of her. The votes are taken by show of hands and that provides additional pressure to conform. If you vote in opposition to the leader, you must do so publicly. However, it is also interesting that the Rangerettes, at least in that year, seemed to be self-governing with, perhaps, the members rather than GND determining who was asked to join (though, again, we don’t know this. It’s likely that the members submitted their choices to GND who then decided if there were people she wanted to add or strike).

Many other scenes show the oddness and humor of the Rangerettes, confirming Erwitt’s vision. These include the girls doing strange theatrical movements, stretching in front of the large dramatic fan, marching to “Hey Look Me Over,” and, of course, the penultimate scene when the girls receive their results.

I love this film. And it’s a true-ish and accurate-ish representation of the Rangerettes in that time and place. Or it’s at least as true and accurate as any other film that could have been made at that time and place. But the most important point (and the reason for showing it) is that it's only one of an infinite number of films that could have been made based on the events of the days Erwitt spent with the Rangerettes. Erwitt chose to shoot certain things and not others. He chose certain shooting angels and not others. He chose which shots to put in the final film and the order in which to present them. All these things comprise the art of making a film. They are necessary, not optional parts of it. Every film, no matter the genre, must be made this way. Thus, in the end, every film represents its director’s (and often producers, editors, etc.) vision and understanding of the world. And we can see that ultimately, this film is representative of Erwitt’s funny, ironic, but ultimately humane view of life.