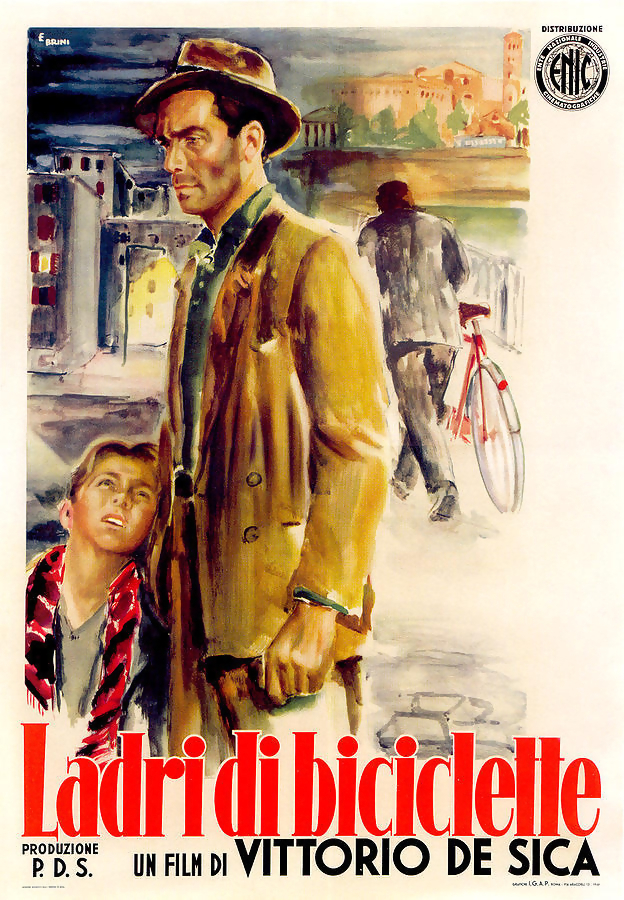

Bicycle Thieves (1948)

Bicycle Thieves might be the most frequently viewed and best remembered film from the Italian Neorealists. It's a deceptively simple film: a man needs his bicycle to work and support his family. The bicycle is stolen from him at the start of his first day of work and he spends the rest of that day and the following day unsuccessfully searching for it. At the end he attempts to steal someone else's bicycle but is unsuccessful and narrowly avoids going to jail. However, this summary of the action of the film really misses the whole point. The central drama of the film is the relationship between Antonio Ricci, whose bicycle is stolen, and his young son Bruno Ricci. Bruno is played by Enzo Staiola. Director Vittorio De Sica had begun filming Bicycle Thieves with the part of Bruno not yet cast. Staiola, at the time 8 years old, was watching the filming on a street corner as he helped his father sell flowers. De Sica noticed him and asked if he would like to be in the movie. It was a good call. Bruno has fewer lines than his father but he pretty much steals every scene. Ultimately, the story of Bicycle Thieves, and the thing that makes it such a great movie is Bruno's changing understanding of who he is and who his father is. However, along the way, De Sica also depicts the gritty desperate world of Roman poverty, the dangers of childhood, the hypocrisy of religion, the vast gulf between the wealthy and the poor, and the alienation of the individual in the crowd.

Bicycle Thieves might be the most frequently viewed and best remembered film from the Italian Neorealists. It's a deceptively simple film: a man needs his bicycle to work and support his family. The bicycle is stolen from him at the start of his first day of work and he spends the rest of that day and the following day unsuccessfully searching for it. At the end he attempts to steal someone else's bicycle but is unsuccessful and narrowly avoids going to jail. However, this summary of the action of the film really misses the whole point. The central drama of the film is the relationship between Antonio Ricci, whose bicycle is stolen, and his young son Bruno Ricci. Bruno is played by Enzo Staiola. Director Vittorio De Sica had begun filming Bicycle Thieves with the part of Bruno not yet cast. Staiola, at the time 8 years old, was watching the filming on a street corner as he helped his father sell flowers. De Sica noticed him and asked if he would like to be in the movie. It was a good call. Bruno has fewer lines than his father but he pretty much steals every scene. Ultimately, the story of Bicycle Thieves, and the thing that makes it such a great movie is Bruno's changing understanding of who he is and who his father is. However, along the way, De Sica also depicts the gritty desperate world of Roman poverty, the dangers of childhood, the hypocrisy of religion, the vast gulf between the wealthy and the poor, and the alienation of the individual in the crowd.

The film opens with a vision of the deep poverty of working men in post WWII Rome. Antonio Ricci can have a job putting up posters if only he can get his bicycle out of hock. With his wife, he pawns his bed sheets, the last thing of any value in their apartment that they can do without. A famous shot shows a man at the pawnbroker's climbing a huge set of shelves filled with pawned bedsheets. Masses of people are so desperately poor that they can no longer afford sheets to sleep on.

The film opens with a vision of the deep poverty of working men in post WWII Rome. Antonio Ricci can have a job putting up posters if only he can get his bicycle out of hock. With his wife, he pawns his bed sheets, the last thing of any value in their apartment that they can do without. A famous shot shows a man at the pawnbroker's climbing a huge set of shelves filled with pawned bedsheets. Masses of people are so desperately poor that they can no longer afford sheets to sleep on.

Right from the beginning Bruno has a lot of character for a child. He complains that there is a scratch on the bicycle and his father should have insisted that the on compensation from the pawn shop. However, for Bruno, the bicycle is the greatest thing ever. He polishes it lovingly. And the next morning he leaves early for work with his father. He is clearly thrilled and equally clearly looks up to his father who, in his spiffy new uniform, seems to Bruno the greatest guy in the world.

Right from the beginning Bruno has a lot of character for a child. He complains that there is a scratch on the bicycle and his father should have insisted that the on compensation from the pawn shop. However, for Bruno, the bicycle is the greatest thing ever. He polishes it lovingly. And the next morning he leaves early for work with his father. He is clearly thrilled and equally clearly looks up to his father who, in his spiffy new uniform, seems to Bruno the greatest guy in the world.

Antonio starts at his new job. But its got to be said that Antonio isn't very good at much of anything. He does a terrible job of getting the poster plastered on the wall and his bicycle is stolen. It's an unkind observation but throughout the movie he's incompetent at everything he attempts, from getting an old man to talk to him, to catching the thief, to stealing a bicycle himself. He's truly an average man with no particular skills. De Sica's triumph is to make Antonio both an individual with a real life and real problems and to make him utterly average so that at the same time he can stand in for workers in general.

Antonio starts at his new job. But its got to be said that Antonio isn't very good at much of anything. He does a terrible job of getting the poster plastered on the wall and his bicycle is stolen. It's an unkind observation but throughout the movie he's incompetent at everything he attempts, from getting an old man to talk to him, to catching the thief, to stealing a bicycle himself. He's truly an average man with no particular skills. De Sica's triumph is to make Antonio both an individual with a real life and real problems and to make him utterly average so that at the same time he can stand in for workers in general.

Antonio first goes to the police but they are involved in meetings and perhaps social events and have no interest in helping him. They take his information but tell him that he'll have to find the bicycle himself. He then goes to a workingmen's organization. Again, they are occupied in social events, rehearsing to put on a play. The leader of the organization offers to help him. Interestingly, the role of the leader is played by Gino Saltamerenda (1902-1951), the only professional actor in the movie. Saltamerenda was also in the earlier neorealist classic Shoeshine (1946). Ironically, at least in my opinion, he's probably the worst actor in Bicycle Thieves. His performance stands out because it lacks the authenticity of Staiola and Maggiorani's performances, or for that matter those of other minor characters.

The workers' efforts to get the bike back come to naught but De Sica uses the scene to put Bruno in the path of a pedophile. In several neorealist films including Germany Year Zero pedophilia is used to illustrate the danger and decadence of society. One element of this and other neorealist films is that the characters hold a stoic, macho image of manhood. This is reinforced by making the pedophile obviously creepy.

The workers' efforts to get the bike back come to naught but De Sica uses the scene to put Bruno in the path of a pedophile. In several neorealist films including Germany Year Zero pedophilia is used to illustrate the danger and decadence of society. One element of this and other neorealist films is that the characters hold a stoic, macho image of manhood. This is reinforced by making the pedophile obviously creepy.

Antonio and his friends extricate Bruno from the pedophile but at this point it begins to rain (the rain was provided by Rome's fire department). We see scenes of people putting away things in the market. Antonio moves in one direction and then another. The rain gets harder. Antonio clearly has no idea what to do. As they run to seek shelter, Bruno falls face down in the street. Antonio doesn't even realize that it has happened. When Bruno tells him what has happened, he shows no sympathy. Bruno's confidence that the bicycle will be found (and that his father knows what to do) is beginning to fail. While they stand against a wall trying to avoid the rain, they are briefly joined by a group of German priests. We'll come back to the issue of Germans in this film a little later. But, note the occurrence here.

Antonio and his friends extricate Bruno from the pedophile but at this point it begins to rain (the rain was provided by Rome's fire department). We see scenes of people putting away things in the market. Antonio moves in one direction and then another. The rain gets harder. Antonio clearly has no idea what to do. As they run to seek shelter, Bruno falls face down in the street. Antonio doesn't even realize that it has happened. When Bruno tells him what has happened, he shows no sympathy. Bruno's confidence that the bicycle will be found (and that his father knows what to do) is beginning to fail. While they stand against a wall trying to avoid the rain, they are briefly joined by a group of German priests. We'll come back to the issue of Germans in this film a little later. But, note the occurrence here.

Antonio and Bruno catch sight of the thief and take off after him. They quickly lose him but follow an old man who has spoken with him into a church. Then we get one of three religious scenes in the movie. In the first one at the start of the film, Bruno's wife Maria visits La Santona, a religious woman who offers advice and prophecy. Maria pays her for advice she previously received.

In the church, we see the rich doing service to the poor... and to is the right word here. They shave the men, then force them to participate in a church service, then feed them (but the food doesn't look too good). They are concerned only with the poor as masses who they herd from place to place. Antonio has a specific problem... he wants to talk to the old man... but none of the wealthy care the slightest about that. They are only interested in the manageable poor. Earlier, Antonio has earlier scoffed at religion. Later, in desperation he returns to La Santona, in hopes that she can tell him how to get his bicycle back. But the advice she provides is not only useless, it's kind of silly. She tells him that he will find it right away or never and refuses to provide elaboration. He leaves in disgust. Religion has failed him.

In the church, we see the rich doing service to the poor... and to is the right word here. They shave the men, then force them to participate in a church service, then feed them (but the food doesn't look too good). They are concerned only with the poor as masses who they herd from place to place. Antonio has a specific problem... he wants to talk to the old man... but none of the wealthy care the slightest about that. They are only interested in the manageable poor. Earlier, Antonio has earlier scoffed at religion. Later, in desperation he returns to La Santona, in hopes that she can tell him how to get his bicycle back. But the advice she provides is not only useless, it's kind of silly. She tells him that he will find it right away or never and refuses to provide elaboration. He leaves in disgust. Religion has failed him.

The pivotal scene in the movie comes after Antonio and Bruno leave the church, having failed to follow the old man. Bruno criticizes Antonio and Antonio slaps him. Bruno's disillusion with his father is now complete. It's not just that Bruno is hurt when his father slaps him. It's far worse. Bruno cries because he's hurt but also because he's lost respect for his father, who has repeatedly failed him. Up to this point, Bruno has tried to keep up with his father, running to be at his side. Now, and for the most of the remaining half hour of the film, he will put physical distance between himself and Antonio. Critically, up until this moment, Bruno, though he has talked back to his father, has run after him like the child he is. For the rest of the movie, Antonio will chase Bruno as if Bruno is the adult and Antonio the child. This begins with Antonio's immediate regret for striking Bruno, but is more than that. Bruno is increasingly the responsible adult and Antonio is increasingly impulsive, childlike, and in need of guidance.

The pivotal scene in the movie comes after Antonio and Bruno leave the church, having failed to follow the old man. Bruno criticizes Antonio and Antonio slaps him. Bruno's disillusion with his father is now complete. It's not just that Bruno is hurt when his father slaps him. It's far worse. Bruno cries because he's hurt but also because he's lost respect for his father, who has repeatedly failed him. Up to this point, Bruno has tried to keep up with his father, running to be at his side. Now, and for the most of the remaining half hour of the film, he will put physical distance between himself and Antonio. Critically, up until this moment, Bruno, though he has talked back to his father, has run after him like the child he is. For the rest of the movie, Antonio will chase Bruno as if Bruno is the adult and Antonio the child. This begins with Antonio's immediate regret for striking Bruno, but is more than that. Bruno is increasingly the responsible adult and Antonio is increasingly impulsive, childlike, and in need of guidance.

It takes the restaurant scene for Bruno's understanding to become more or less complete. First, Antonio's behavior at the restaurant is strange. Bruno is, after all, a young child, 10 at the most. Antonio buys him wine and proposes they get drunk together. Children being permitted to drink a little wine is much more common in Italy than in the US but 10 year olds don't get drunk with their fathers. Antonio then explains his finances to Bruno, again, not appropriate. But perhaps even more important than Antonio's strange behavior is the fact that neither Antonio nor, especially Bruno knows how to behave in a restaurant. Antonio has come to the restaurant seeking pizza not realizing that the restaurant doesn't serve it. Bruno compares himself and his father to the wealthy family eating at the adjacent table. For them, eating at a restaurant is clearly routine. Bruno literally doesn't know how to eat. He has no idea how to use a knife and fork (probably at home he and his parents eat with spoons or their hands, this would have been common among the mid 20th century Italian poor). The wealthy boy has a multi-course meal which he knows how to eat. He looks at Bruno with open scorn. Up to this point, Bruno has lived in his parents' world and in his neighborhood. That is his whole experience. Now, at the restaurant, he glimpses the wider world and, in a flash, understands his place in it. He is a poor boy from a poor family. His father has very limited abilities and possibilities. He'll never be able to eat like the rich boy and he'll never earn that boy's respect.

It takes the restaurant scene for Bruno's understanding to become more or less complete. First, Antonio's behavior at the restaurant is strange. Bruno is, after all, a young child, 10 at the most. Antonio buys him wine and proposes they get drunk together. Children being permitted to drink a little wine is much more common in Italy than in the US but 10 year olds don't get drunk with their fathers. Antonio then explains his finances to Bruno, again, not appropriate. But perhaps even more important than Antonio's strange behavior is the fact that neither Antonio nor, especially Bruno knows how to behave in a restaurant. Antonio has come to the restaurant seeking pizza not realizing that the restaurant doesn't serve it. Bruno compares himself and his father to the wealthy family eating at the adjacent table. For them, eating at a restaurant is clearly routine. Bruno literally doesn't know how to eat. He has no idea how to use a knife and fork (probably at home he and his parents eat with spoons or their hands, this would have been common among the mid 20th century Italian poor). The wealthy boy has a multi-course meal which he knows how to eat. He looks at Bruno with open scorn. Up to this point, Bruno has lived in his parents' world and in his neighborhood. That is his whole experience. Now, at the restaurant, he glimpses the wider world and, in a flash, understands his place in it. He is a poor boy from a poor family. His father has very limited abilities and possibilities. He'll never be able to eat like the rich boy and he'll never earn that boy's respect.

A few scenes later Antonio and Bruno catch sight of the thief and chase him down. I'll discuss what happens in a moment but let's take a digression to talk about the thief's hat. At several points in the film the dialog notes that the thief has a German hat. That is, he's wearing a German WWII soldier's hat. Germans also appear as a group of priests earlier in the film. In this film, the connection of Germany with evil and with privilege is muted but it's there. The thief has the German hat, Antonio the good honest Italian style hat. This would be trivial EXCEPT for the fact that other neorealist films, particularly Rome Open City, Germany Year Zero, and Paisan explicitly do the same thing in ways that are much more central to the plot. That is, they equate Germany and Germans with fascism and evil while essentially giving Italians a free pass. They do not confront the fact that Italy was a fascist society far longer than Germany and that although the crimes of Italian fascists pale when compared with the crimes of the Nazis, they were nonetheless brutal. Italian fascists tortured and murdered their enemies. They led a regime of hyper-nationalism that continually applied brutal violence to enact their vision of society, imprisoning and killing those who dared to speak against them. Mussolini was absolutely cut from the same cloth as Hitler. IMHO Italians have, to this day, never really confronted this past. Neorealist movies, for all their grit, truthfulness, and cinematic power, whitewashed Italian fascism and helped Italians to forget or ignore their own involvement in it.*

A few scenes later Antonio and Bruno catch sight of the thief and chase him down. I'll discuss what happens in a moment but let's take a digression to talk about the thief's hat. At several points in the film the dialog notes that the thief has a German hat. That is, he's wearing a German WWII soldier's hat. Germans also appear as a group of priests earlier in the film. In this film, the connection of Germany with evil and with privilege is muted but it's there. The thief has the German hat, Antonio the good honest Italian style hat. This would be trivial EXCEPT for the fact that other neorealist films, particularly Rome Open City, Germany Year Zero, and Paisan explicitly do the same thing in ways that are much more central to the plot. That is, they equate Germany and Germans with fascism and evil while essentially giving Italians a free pass. They do not confront the fact that Italy was a fascist society far longer than Germany and that although the crimes of Italian fascists pale when compared with the crimes of the Nazis, they were nonetheless brutal. Italian fascists tortured and murdered their enemies. They led a regime of hyper-nationalism that continually applied brutal violence to enact their vision of society, imprisoning and killing those who dared to speak against them. Mussolini was absolutely cut from the same cloth as Hitler. IMHO Italians have, to this day, never really confronted this past. Neorealist movies, for all their grit, truthfulness, and cinematic power, whitewashed Italian fascism and helped Italians to forget or ignore their own involvement in it.*

Returning to the main plot line, when Antonio and Bruno catch up with the thief they find him well defended by the men of his neighborhood. Bruno, now taking the adult role, goes for the cops while Antonio grabs the thief, who has a seizure. After the cop arrives, they search the thief's apartment, finding nothing except a pair of probably stolen automobile tires. However, the take-away from this scene is that the thief is a pathetic character who is even more impoverished than Antonio and Bruno. The thief's apartment is smaller, dirtier, and far more miserable than the Ricci's apartment. So, although we don't feel great sympathy for the thief (and Antonio does, of course, have the right man) we can see this is a case of an impoverished man robbed by one who is even more impoverished. And once again, Antonio has failed...

Returning to the main plot line, when Antonio and Bruno catch up with the thief they find him well defended by the men of his neighborhood. Bruno, now taking the adult role, goes for the cops while Antonio grabs the thief, who has a seizure. After the cop arrives, they search the thief's apartment, finding nothing except a pair of probably stolen automobile tires. However, the take-away from this scene is that the thief is a pathetic character who is even more impoverished than Antonio and Bruno. The thief's apartment is smaller, dirtier, and far more miserable than the Ricci's apartment. So, although we don't feel great sympathy for the thief (and Antonio does, of course, have the right man) we can see this is a case of an impoverished man robbed by one who is even more impoverished. And once again, Antonio has failed...

Then we come to the penultimate scene of the film. Antonio and Bruno walk to the football stadium where a big game is being played. They pass hundreds of bicycles. Bruno sits dejectedly on the curb while Antonio alternately sits and paces, eying an unattended bicycle. Bruno feels the weight of the day and of his new understanding of his father and of himself as well. As the match ends and the fans leave, Antonio, surrounded by people on bicycles decides to steal the bicycle he's been looking at. However, as soon as he does so he is chased by the crowd and soon caught. The bicycle's owners says to Antonio exactly the same thing that Antonio would have said to the man who stole his bicycle (and does say to various others), that the loss of his bicycle would ruin him. Antonio has attempted to steal from another very poor man, making him just the same as the thief who stole from him. Bruno's presence is critical in getting the victim not to take Antonio to the police.

Then we come to the penultimate scene of the film. Antonio and Bruno walk to the football stadium where a big game is being played. They pass hundreds of bicycles. Bruno sits dejectedly on the curb while Antonio alternately sits and paces, eying an unattended bicycle. Bruno feels the weight of the day and of his new understanding of his father and of himself as well. As the match ends and the fans leave, Antonio, surrounded by people on bicycles decides to steal the bicycle he's been looking at. However, as soon as he does so he is chased by the crowd and soon caught. The bicycle's owners says to Antonio exactly the same thing that Antonio would have said to the man who stole his bicycle (and does say to various others), that the loss of his bicycle would ruin him. Antonio has attempted to steal from another very poor man, making him just the same as the thief who stole from him. Bruno's presence is critical in getting the victim not to take Antonio to the police.

This leads us to the final scene of the movie. Antonio and Bruno join a mass of people slowly walking away. Both are crushed. Antonio is on the edge of tears. They walk side by side, not touching, still alienated from each other. Then Bruno looks up at his devastated father and takes his hand. It's now a far older and far wiser Bruno who accepts and comforts his father.

This leads us to the final scene of the movie. Antonio and Bruno join a mass of people slowly walking away. Both are crushed. Antonio is on the edge of tears. They walk side by side, not touching, still alienated from each other. Then Bruno looks up at his devastated father and takes his hand. It's now a far older and far wiser Bruno who accepts and comforts his father.

It's easy to see why films like Bicycle Thieves made such a profound impact, not only in Italy but around the world. In Italy, films had been almost totally devoted to distraction since the rise of Mussolini in 1922 but around the world, during WWII most films were devoted to propaganda and entertainment. There were undoubtedly some great movies but there weren't many that truly felt authentic. Bicycle Thieves gives the impression of saying something real, something difficult. It eschews happy endings. People have been through years of horror and misery. They've known impoverishment, death, and destruction. Now, for virtually the first time, many people saw this reflected back on them in movies. Further, as I noted above, for Italians, this tough reality also falsely suggested that they were the people who had suffered. They, rather than the people they brutalized and oppressed, were the victims. The film exculpated them for the crimes committed by Italian fascists.

The era of Neorealism was brief, really only from 1945 to 1949 when the Andreotti law made it difficult to make films as critical of society as these. But, in addition to becoming more difficult to make, audiences had a limited capacity to absorb this kind of movie making. Authenticity is great but you don't want it all the time. Additionally, economic conditions were changing. Europe was destroyed by WWII, but with lots of US help (through The Marshall Plan) it began rebuilding rapidly. By the early 1950s poverty and unemployment were very much diminished and Italians were shopping for cars not pawning bedsheets to get bicycles out of hock. By 1960, the most famous film was La Dolce Vita (The good life). Of course, that's not really a film about how wonderful things are either.

*I am aware (as you should be too) that the same can be said of American movies, even the most realistic of which have usually failed to take on this country's legacy of slavery, genocide, misbegotten militarism, colonialism, and so on. However, neorealist films are widely praised for their feeling of reality. For their audiences in the 1940s they seemed to truly tell it like it is. For that reason we need to be particularly clear about this gigantic hole in their depiction of postwar Italy.

Next: Film Noir