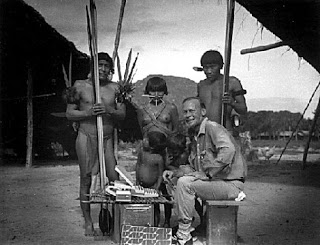

Doing Fieldwork Among the Yanomamo in the 1960s

Napoleon Chagnon's account of his first visit to a Yanomamo Village.

The entrance to the village was covered over with brush and dry palm

leaves. We pushed them aside to expose the low opening to the

village. The excitement of meeting my first Yanomamo was almost unbearable

as I duck-waddled through the low passage into the village clearing.

The entrance to the village was covered over with brush and dry palm

leaves. We pushed them aside to expose the low opening to the

village. The excitement of meeting my first Yanomamo was almost unbearable

as I duck-waddled through the low passage into the village clearing.

I looked up and gasped when I saw a dozen burly, naked, sweaty, hideous men staring at us down the shafts of their drawn arrows! Immense wads of green tobacco were stuck between their lower teeth and lips making them look even more hideous, and strands of dark-green slime dripped or hung from their nostrils-strands so long that they clung to their pectoral muscles or drizzled down their chins. My next discovery was that there were a dozen or so vicious, underfed dogs snapping at my legs, circling me as if I were going to be their next meal. I just stood there holding my notebook helpless and pathetic. Then the stench of the decaying vegetation and filth hit me and I almost got sick. I was horrified. What kind of welcome was this for the person who came here to live with you and learn your way of life, to become friends with you.

Next: learning culture

Napoleon Chagnon, Yanomamo: The Fierce People. First edition, 1968. Chagnon (1938-2019) was an important and extremely controversial figure in anthropology. His book about the Yanomamo, published under various titles went to 6 editions, and was one of the most widely read descriptions of a single culture in anthropology from its original publication until at least the early 2000s. The passage above is from the first chapter of the book. There, Chagnon described how he arrived in Yanomamo society and the various things he did to be accepted by the Yanomamo. Much of what Chagnon tells us about this process might strike modern readers (and most modern anthropologists) as of dubious morality. Chagnon was also controversial because of his advocacy of biologically based explanations of social phenomena. In the early 2000s, he was falsely accused of being responsible for a genocide of the Yanomami caused by a live measles vaccine. That this false accusation gained much publicity within the American Anthropological Association probably reflected the relatively low opinion that many anthropologists had of Chagnon's work at that time.